Tayeb Salih’s Season of Migration to the North is a lyrical, sensuous postcolonial novel that takes place in a small Sudanese village. If you’ve read Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, you’ll recognize several of the novels themes, which include racism, sexism, corruption, and moral decay. The key difference is that Salih’s work is taken from the perspective of the colonized rather than that of the colonizers. The central figure, Mustafa Sa’eed, draws on the eroticism of his African Muslim background to seduce several European women while studying abroad in England. In this way he manages to enslave and brutalize Northerners, reversing the traditional roles of colonized and colonizer.

Mustafa Sa’eed is to Conrad’s Kurtz as Salih’s narrator is to Conrad’s Marlow. The unnamed narrator in this novel is a “secret sharer” of the central figure’s life story, much as Marlow is privy to the details of Kurtz’s life. Mustafa Sa’eed entices the narrator with an incomplete version of his sexual escapades in England, and after his death, establishes the narrator as the guardian of his children. This irrevocably links the narrator’s life with Sa’eed’s. As more details of Sa’eed’s life become apparent after his death, the narrator is slowly driven insane by the likeness of Sa’eed’s life to his own. Also educated in England, the narrator becomes torn between the tensions between South and North, hot and cold, passion and apathy. He finally decides to live individualistically, without concern for the similarities between himself and Mustafa Sa’eed, but this decision may have come too late.

One major theme of this novel is the failure of postcolonial government in Sudan. Salih describes a fictional (though certainly not fantastical) Minister of Education, who says that farmers and peasants should not be educated “beyond their means.” He claims that education will result in unrealistic aspirations to become a part of the bourgeoisie. Meanwhile, the Minister vacations on a yacht, wears expensive jeweled rings, and flies in dresses from Harrod’s on a private jet for his wife. The novel also stresses that education does not necessarily lead to action, particularly in political affairs. The narrator, educated in British schools and working in the postcolonial government, is unable to create tangible changes in his native village. Meanwhile, his friend Mahjoub, who only passed through secondary school, leads the village Commission and brings improvements to the people’s quality of life.

Another theme is the tension between tradition and modernity, particularly relative to sexuality and marriage. The narrator falls in love with Sa’eed’s widow, Hosna, after his death, but lacks the courage to marry her. While he leaves the village on government affairs, a 70-year-old man claims her as his second wife against her will. She is forced to marry under the edict of her father and the village elders. Moreover, female circumcision is traditionally performed in the village and upheld by elders.

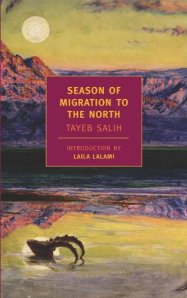

The poetic quality of this book is most impressive. The version that I read, the Heinemann edition, was translated from Arabic brilliantly by Denys Johnson-Davies and retains a lovely, lyrical luster. I highly recommend purchasing this edition for a couple of dollars on Amazon. Although Tayeb Salih’s prose sometimes borders on overkill, he knows precisely when to reign it in. The story is gripping apart from its poetic qualities. This is a novel packed with action, violence, and lust, among many other powerful emotions that keep readers engrossed throughout.